Over the past few years I've been migrating from building apps on Rails and deploying them on Dokku (a self-hosted Heroku alternative) to building apps on Next.js and deploying them on Firebase: a platform-as-a-service (PaaS) offering from Google to build web and mobile apps.

This page includes a brief explanation of why I think these technology choices are currently the best way to build web apps. After that I'll explain with minimal necessary detail how to use the important parts of Firebase assuming you have a working knowledge of Javascript, databases, and web apps.

Why Firebase? #

I first learned web development in the early 2010s with Ruby on Rails, a wonderful monolithic opinionated web framework used by companies like GitHub, Shopify, and Basecamp. I don't think Rails-like frameworks (including Laravel, Django, and Phoenix) are a bad choice if you're building an app today. I used it to build Fileinbox, a small SaaS app that's made me $591.8K as of 2023.

That said, as a mostly solo developer I've been so much happier building apps with Next.js and Firebase. To reach the next stage of growth for Fileinbox I've decided to completely rewrite it for Firebase.

Here's why:

- Ongoing maintenance is effectively zero. There are apps I've built on this stack that I haven't touched for years that are happily chugging along, including mission-critical projects I've built for other people as a consultant. Invariably on my Rails stack something would break in a project every few months in the complexity of SSL certificates, servers, Postgres databases, DNS, or the VPS. Because Firebase is completely owning the backend complexity of authentication, authorization, data storage, and hosting I don't have to think about any of it. I feel like I'm free to just work on the frontend and I get backend and devops powers for free. I've essentially hired Google to be my sysadmin and devops team.

- security updates

- My costs are way down. Instead of paying a monthly fee for a certain size of database and then manually upgrading it, I just pay a fraction of a penny per read and write. Instead of buying a dedicated VPS I just pay a fraction of a penny per 100ms of runtime. As long as I'm building things that are making money I can essentially stop thinking about what apps cost to run: as soon as the cost becomes anything meaningful (>$10/month) my usage would be so incredibly high that I'd be making way more than that (unless my business model was fundamentally broken).

- where does this break down? high number of writes?

- I can build more complicated things. Realtime updates, backend video processing and job queueing, cron jobs, 3rd party OAuth logins, sending templated emails and SMS messages, and integrating Stripe subscriptions used to be a huge pain (I remember in particular reading an entire book on how to properly integrate Stripe with Rails). On Firebase they're trivial and fun (integrating Stripe subscriptions on Firebase takes about ten minutes and just works).

- what's the ramp up time to get there?

Disadvantages include:

- Vendor lock-in with Google, and Google is particularly notorious for shutting down services with little notice. My backup plan here is to migrate to something like Supabase but that wouldn't be trivial.

- other alternatives?

- Firestore is severely limited. You can't query documents on more than two attributes at a time, you can't run queries that join multiple documents, XXXXX. You'll need to start thinking in NoSQL: denormalize, think about the querying you'll need to do when designing your database, and XXX.

- specific examples: full text search, date filtering?

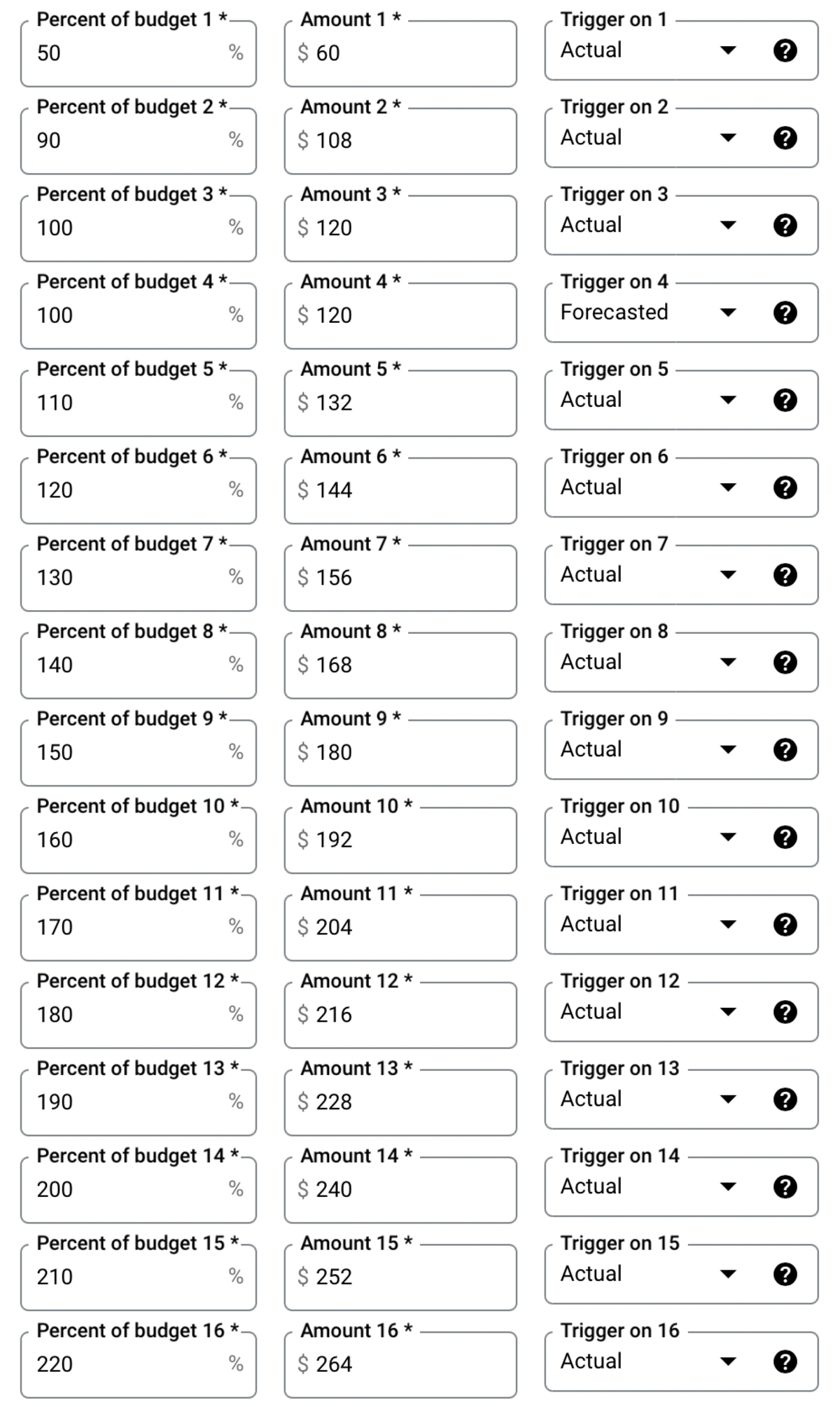

- There's a danger of a gigantic bill. Everything about Firebase can scale practically to infinity. Like all serverless offerings there are horror stories of developers getting massive bills because of bugs in their code. Unfortunately there's not a straightforward way to set up a kill switch if your spending crosses a certain amount. The official guidelines for managing spending recommend setting up billing alerts. I personally have these alerts going to my wife and assistant and pushed directly to my Apple Watch via. Pushover so that hopefully if there's a runaway bill it will get caught by somebody quickly.

My billing alerts include notifications every 10% after 100% up to 200%

Automatically stop billing after a certain threshold, or shut down all functions: https://cloud.google.com/billing/docs/how-to/notify#cap_disable_billing_to_stop_usage

Discussions:

- https://www.reddit.com/r/Firebase/comments/lpudjk/for_real_though_billing_limits/

- https://stackoverflow.com/questions/67731470/firebase-billing-kill-switch

- https://stackoverflow.com/questions/52324299/is-there-a-way-to-limit-firebases-blaze-plan

How to use Firebase #

0. What we won't cover #

Hosting (use vercel), crashlytics, FCM, remote config, ab testing, dynamic links, predictions, app distribution, anything mobile

1. Setting Up a Firebase Project and Using the Emulator #

v9 #

In August 2021 Google introduced the v9 version of the Firebase library for Javascript. This version of the SDK is designed in a more functional style which enables tree shaking to minimize unused code.

In my opinion this change has been kind of a pain but here we are. You may see still see code floating around Stack Overflow in the old style that looks like this:

import firebase from "firebase/app";

import "firebase/firestore";

const db = firebase.firestore();

const userDoc = db.collection("users").doc("user1");

userDoc.set({

name: "John Doe",

email: "john@example.com",

points: 100,

});The newer v9 version (and the version used in this post) to do the same thing would look like this:

import { doc, setDoc, getFirestore } from "firebase/firestore";

const db = getFirestore();

const userDoc = doc(db, "users", "user1");

setDoc(userDoc, {

name: "John Doe",

email: "john@example.com",

points: 100,

});Except, confusingly, when using firebase-admin which we'll talk about in the Firebase Serverless Functions part. For that we're still on the pre-v9 style.

2. Firestore #

2.1 Introduction to Firestore #

Cloud Firestore is a NoSQL document-based scalable real-time database hosted by Google.

It’s the most convenient way I’ve found to add a database to web apps. When combined with other products from Firebase it’s powerful enough to completely remove the need for a traditional backend like Rails, Django, or Laravel.

When using Firestore you’ll never have to worry about scaling, uptime, replication, or other headaches you’ll run into when using traditional databases. As long as you architect your app in a way that avoids triggering recursive writes (we’ll cover this in the Cloud Functions section) Firestore will (probably) be much cheaper than using a regular database.

My experience with using it has been blissful. It has some serious limits that need to be worked around but if you can design your web apps with Firestore in mind the database layer requires much less ongoing thought in the app building and maintenance process. Plus, you get real-time updates and nearly infinite scaling practically for free!

2.2 Writing a Document #

Firestore holds Collections of Documents. Documents can contain Collections.

You can think of a Document as a JSON object. Firestore documents can hold strings, numbers, booleans, dates, and null as well as maps, arrays, references to other documents, and geographical points.

Here's how to write a document:

import { getFirestore, doc, setDoc } from "firebase/firestore";

const db = getFirestore();

const postRef = doc(db, "posts", "myPostId");

await setDoc(postRef, {

title: "My First Blog Post",

views: 150,

isPublished: true,

publishedAt: new Date(),

owner: null,

metadata: {

author: "Christian",

},

tags: ["tag1", "tag2", "tag3"],

// author: authorRef,

// location: new GeoPoint(37.422, 122.084),

});Note that we don't have to define any sort of schema for which keys in this collection will contain values that will be a certain type. We just set a JSON object at a document path! Firestore is extremely flexible in this way. You can decide to add collections or attributes to documents on the fly and it just works.

Every 100k document writes costs $0.18.

In the above code I specified an ID for this document (myPostId) but we also could’ve added a document to a Collection and gotten an automatically generated ID, like this:

import { getFirestore, collection, addDoc } from "firebase/firestore";

const db = getFirestore();

const postsRef = doc(db, "posts");

await addDoc(postRef, { title: "My post" });2.3 Reading a Document #

Uncommonly you’ll want to read a document a single time like this:

import { getFirestore, doc, getDoc } from "firebase/firestore";

const db = getFirestore();

const postRef = doc(db, "posts", "myPostId");

const postSnap = await getDoc(postRef);

const post = postSnap.data();More commonly you’ll want to read a document and keep it updated if it changes, like this:

import { getFirestore, doc, onSnapshot } from "firebase/firestore";

const db = getFirestore();

const postRef = doc(db, "posts", "myPostId");

const unsubscribe = onSnapshot(postRef, (postSnap) => {

const post = postSnap.data();

});Even more commonly you’ll just read data from a Firebase React hook with something like const { data: post } = useDoc(/posts/myPostId")

2.4 Updating a Document #

To upsert a Document (ie: create it if it doesn’t exist and update it if it does) use:

import { getFirestore, doc, setDoc } from "firebase/firestore";

const db = getFirestore();

const postRef = doc(db, "posts", "myPostId");

await setDoc(postRef, { views: 151 }, { merge: true });To update an existing document (and fail if the document doesn’t exist) use:

import { getFirestore, doc, updateDoc } from "firebase/firestore";

const db = getFirestore();

const postRef = doc(db, "posts", "myPostId");

await updateDoc(postRef, { views: 151 });There are a handful of special values (known as Field Values) that you can include as attributes when updating a Document to avoid race conditions. They are:

increment(n): increases or decreases a numeric field by the specified amountn. If the field doesn't exist, it sets the field to the specified value.arrayUnion(...elements): adds elements to an array if they aren’t already present or (if the key doesn't exist) creates an array with the specified valuesarrayRemove(...elements): removes the specified elements from an array field. If the field doesn't exist, it does nothing.

Two other useful Field Values are:

serverTimestamp(): the current server timestampdeleteField(): deletes the key with this value

Here's how we might use Field Values to update a document:

import {

getFirestore,

doc,

updateDoc,

getFirestore,

deleteField,

serverTimestamp,

arrayUnion,

increment,

} from "firebase/firestore";

const db = getFirestore();

const postRef = doc(db, "posts", "myPostId");

updateDoc(postRef, {

updatedAt: serverTimestamp(),

tags: arrayUnion("newTag"),

views: increment(1),

owner: deleteField(),

});2.6 Writing Multiple Documents in a Batch and Transaction #

There are two ways to perform bulk writes of documents to Firestore: batches and transactions. Neither is billed differently than if you wrote documents one at a time but:

- Batches and transactions are more network efficient

- Batches and transactions ensure that either all of the writes succeed or they all fail

Batches simply group set or update actions:

import { getFirestore, doc, writeBatch } from "firebase/firestore";

const db = getFirestore();

const batch = writeBatch(db);

const post1Ref = doc(db, "posts", "1");

const post2Ref = doc(db, "posts", "2");

batch.set(post1Ref, { title: "Post 1" });

batch.set(post2Ref, { title: "Post 2" }, { merge: true });

await batch.commit();Transactions group reads and set or update actions for writes that depend on data from other documents:

import { getFirestore, doc, runTransaction } from "firebase/firestore";

const db = getFirestore();

const fromUserRef = doc(db, "users", "1");

const toUserRef = doc(db, "users", "2");

const points = 100;

await runTransaction(db, async (transaction) => {

const fromUserSnap = await transaction.get(fromUserRef);

const toUserSnap = await transaction.get(toUserRef);

if (!fromUserSnap.exists()) throw "From User does not exist!";

if (!toUserSnap.exists()) throw "To User does not exist!";

if (fromUserSnap.data().points < points) throw "Not enough points!";

transaction.update(fromUserRef, {

points: fromUserSnap.data().points - points,

});

transaction.update(toUserRef, { points: toUserSnap.data().points + points });

});In a transaction, if one of the read documents changes while the writes are being performed the transaction will start over.

2.7 Reading a Collection #

const usersCollectionRef = collection(db, "users");

const userSnapshot = await getDocs(usersCollectionRef);

const userList = userSnapshot.docs.map((doc) => doc.data());Hook

2.9 Querying and sorting #

Here’s where the limits of Firestore get spooky. If you’re coming from any sort of SQL database these limits may feel like dealbreakers. I encourage you to sit with the unfamiliarity until you’ve considered how you might get your job done with Firestore before jumping ship. In practice I haven’t yet found an application that couldn’t be modeled entirely within Firebase.

If you really need a way to query data in your app that Firestore doesn’t support, most commonly full text search, you can probably get there with an extension.

Alright let’s rip this bandaid off. With Firestore you can’t:

- query or sort more than two fields at a time (and querying more than one field will require explicitly creating an index)

- do case insensitive searches (instead, save the field again downcased under a new key)

- join documents (instead, denormalize the data you need)

- use inequality operations on more than one field at a time

- use OR. Instead, write two queries

Still with me? Cool. Here’s how to do a basic query:

import {

collection,

query,

where,

getDocs,

getFirestore,

} from "firebase/firestore";

const db = getFirestore();

const usersRef = collection(db, "users");

const q = query(usersRef, where("points", ">", 100));

const querySnapshot = await getDocs(q);

const users = querySnapshot.docs.map((doc) => doc.data());where() conditions:==, !=, <, <=, >, >=, array-contains, array-contains-any, in, not-in

If you try to do multiple fields you’ll get a link to make an index

Ordering

Pagination #

Limit Start at, startAftwe, end at, end before

Document count

2.12 Creating an Index #

2.13 Limits of Querying #

2.14 Deleting Documents #

TTL

2.15 Deleting Nested Collections #

2.10 Data Modeling #

A common pattern I’ve used that makes writing security rules straightforward is having a top level users collection that stores user Documents, then storing application data specific to that user as a sub collection on the user document.

2.16 Security Rules #

2.17 Backups #

2.18 Pricing #

3. Firebase Authentication #

3.1 Introduction #

3.2 Setting Up Firebase Authentication #

3.3 Email/Password Authentication #

3.4 Logging Out Users #

3.5 Third-Party Authentication Providers #

3.6 Deleting User Accounts #

3.7 Deleting User Data with Accounts #

3.8 Linking Authentication with Firestore #

3.9 Understanding and Handling Authentication Errors #

4. Firebase Cloud Storage #

4.1 Introduction to Firebase Cloud Storage #

4.2 Creating Buckets and the Default Bucket #

4.3 Understanding Bucket Tiers and Locations #

4.4 Uploading an Object #

4.5 Downloading an Object #

4.6 Creating Public Links #

4.7 Deleting an Object #

4.8 Firebase Cloud Storage Pricing #

4.9 Security Rules for Firebase Cloud Storage #

5. Firebase Serverless Functions #

5.1 Introduction to Firebase Serverless Functions #

v1 vs. v2

5.2 Setting Up a Firebase Functions Project and Using the Emulator #

5.3 Setup and Deployment of Firebase Functions #

5.4 HTTPS Triggers #

5.5 Reading and Writing to Firestore from Functions #

5.6 Firestore Triggers: onCreate and onDelete #

5.7 Firestore Triggers: onUpdate #

5.8 Auth Triggers #

5.9 Callable Functions #

5.10 Scheduled Functions #

5.11 Understanding Cold Starts #

5.12 Testing and Debugging Functions #

5.13 Managing Dependencies in Firebase Functions #

5.14 Error Handling in Firebase Functions #

Access to fetch at 'http://localhost:5001/fileinbox-4e544/us-central1/gdrivegetaccountinfo' from origin 'http://localhost:3000' has been blocked by CORS policy: Response to preflight request doesn't pass access control check: No 'Access-Control-Allow-Origin' header is present on the requested resource. If an opaque response serves your needs, set the request's mode to 'no-cors' to fetch the resource with CORS disabled.

5.15 Monitoring and Logging #

5.16 Firebase Serverless Functions Pricing #

6. Firebase Analytics #

6.1 Introduction to Firebase Analytics #

6.2 Setting Up Firebase Analytics #

6.3 Events in Firebase Analytics #

6.4 Tracking Signup Conversion Percentage #

6.5 Tracking Trial to Paid Conversions #

6.6 Measuring User Activation #

6.7 Monitoring Onboarding #

6.8 User Properties and Audiences #

6.9 Reporting and Dashboards #

6.10 Integrations with Other Firebase Services #

6.11 Firebase Analytics Pricing #

7. Firebase Plugins #

7.1 Introduction to Firebase Plugins #

7.2 Sending Emails with Firebase #

7.3 Making Email Templates #

7.4 Sending SMS and MMS Messages with Twilio #

7.5 SaaS Billing with the Stripe Plugin #

7.6 Image Manipulation with ImageMagick #

7.7 Full Text Search with Algolia #

7.8 Machine Learning with ML Kit #

7.9 Using Firebase Cloud Messaging for Notifications #

Firestore #

Batch writes #

https://googleapis.dev/nodejs/firestore/latest/Firestore.html#bulkWriter

Recursive deletes (delete a doc and its subcollections) #

Only works on the backend:

await firestore.recursiveDelete(docRef);Google Cloud Storage #

Frustratingly if you include a leading / in the path of your objects you upload Google Cloud Storage will create a new folder called / in your root directory.

Make sure you don't include a leading slash in your path or you'll be very confused for a long time when your files aren't actually where you think they are:

const { Storage } = require("@google-cloud/storage");

const gcs = new Storage();

const bucketName = "project-id.appspot.com";

const bucket = gcs.bucket(bucketName);

const data = "important data";

const badPath = `/no/wrong/bad/data.txt`;

const goodPath = `yes/correct/data.txt`;

await bucket.file(goodPath).save(data);Firebase Cloud Functions #

Set timeout and memory allocation #

exports.doSomething = functions

.runWith({

timeoutSeconds: 9 * 60,

memory: "1GB",

})

.firestore.document("collection/{docId}")

.onCreate(doSomething);Available options for memory (and accompanying CPU speed) are:

- 128MB — 200MHz

- 256MB — 400MHz

- 512MB — 800MHz

- 1GB — 1.4 GHz

- 2GB — 2.4 GHz

- 4GB — 4.8 GHz

- 8GB — 4.8 GHz

Source: https://firebase.google.com/docs/functions/manage-functions#set_timeout_and_memory_allocation

Environment Variables #

Instead of the old way of adding variables to functions.config(), add environment variables to functions/.env and check them into version control:

DROPBOX_KEY="foobarbaz"Environment variables are synced with firebase when you deploy your firebase cloud functions with firebase deploy --only functions.

Secrets #

Set secrets with firebase functions:secrets:set SECRET_NAME. Destroy them with functions:secrets:destroy SECRET_NAME.

Access secrets in your functions as regular environment variables: process.env.SECRET_NAME

Make sure to explicitly whitelist the secret name for each function that uses it:

exports.myFunction = functions

.runWith({

secrets: ["SECRET_NAME"],

})

.https.onRequest(myFunction);Remove cold start delay #

To remove the cold start delay on cloud functions you need an instance running all the time:

exports.foo = functions.runWith({ minInstances: 1 }).https.onRequest(foo);You'll always have an instance running which based on the google cloud pricing will cost no more than:

- 128MB — 200MHz:

0.000000231 * 10 * 60 * 60 * 24 * 30 =$5.98/month - 256MB — 400MHz:

0.000000463 * 10 * 60 * 60 * 24 * 30 =$12.00/month - 512MB — 800MHz:

0.000000925 * 10 * 60 * 60 * 24 * 30 =$23.98/month - 1GB — 1.40 GHz:

0.000001650 * 10 * 60 * 60 * 24 * 30 =$42.76/month - 2GB — 2.40 GHz:

0.000002900 * 10 * 60 * 60 * 24 * 30 =$75.16/month - 4GB — 4.80 GHz:

0.000005800 * 10 * 60 * 60 * 24 * 30 =$150.33/month - 8GB — 4.80 GHz:

0.000006800 * 10 * 60 * 60 * 24 * 30 =$176.25/month

There are some free tier and sustained use discounts I don't totally understand.

Note that functions running in some regions are cheaper than others. us-central1 is one of the cheaper Tier 1 regions.

Deploying #

Functions deploy had errors with the following functions

#

Try:

- checking the output of

firebase --debug deploy --only functions - checking the output of

firebase functions:log - deleting the

us.artifacts.[Project ID].appspot.combucket in the Cloud Storage page on Google Cloud Platform.

Sources: